9 min to read

Design patterns!

Design patterns

To develop quality applications we will need to have a good knowledge of existing design patterns, so we can recognize when it is possible to use them in our projects. Design patterns arise to help us solve common development tasks in a specific way, so that we do not reinvent the wheel, we learn and promote good practices, standardize the resolution of certain problems, etc. They are also classified into 3 categories: creative, structural and behavioral. Also, in today’s post I’m going to relate some patterns to Angular projects.

MVC-MVVM pattern

The MVC design pattern refers to the architecture of our app, where there are three distinct parts.

Models are used to represent the data (e.g. interface or class without logic).

Views correspond to the user interface (the HTML model).

Finally the controllers/components allow to link the two previous layers.

However, as we know, Angular supports two-way data binding, so we could say that we are actually using MVVM (Model-View-ViewModel).

Here I leave you more complementary info on this.

Dependency injection pattern

Dependency injection (DI) is an important design pattern for large-scale application development. Angular has its own DI system, which increases efficiency and scalability. If you remember, in the constructors of our classes (components, directives, services) dependencies (services or objects) are injected, as well as these can be provided. Some examples from the official guide here.

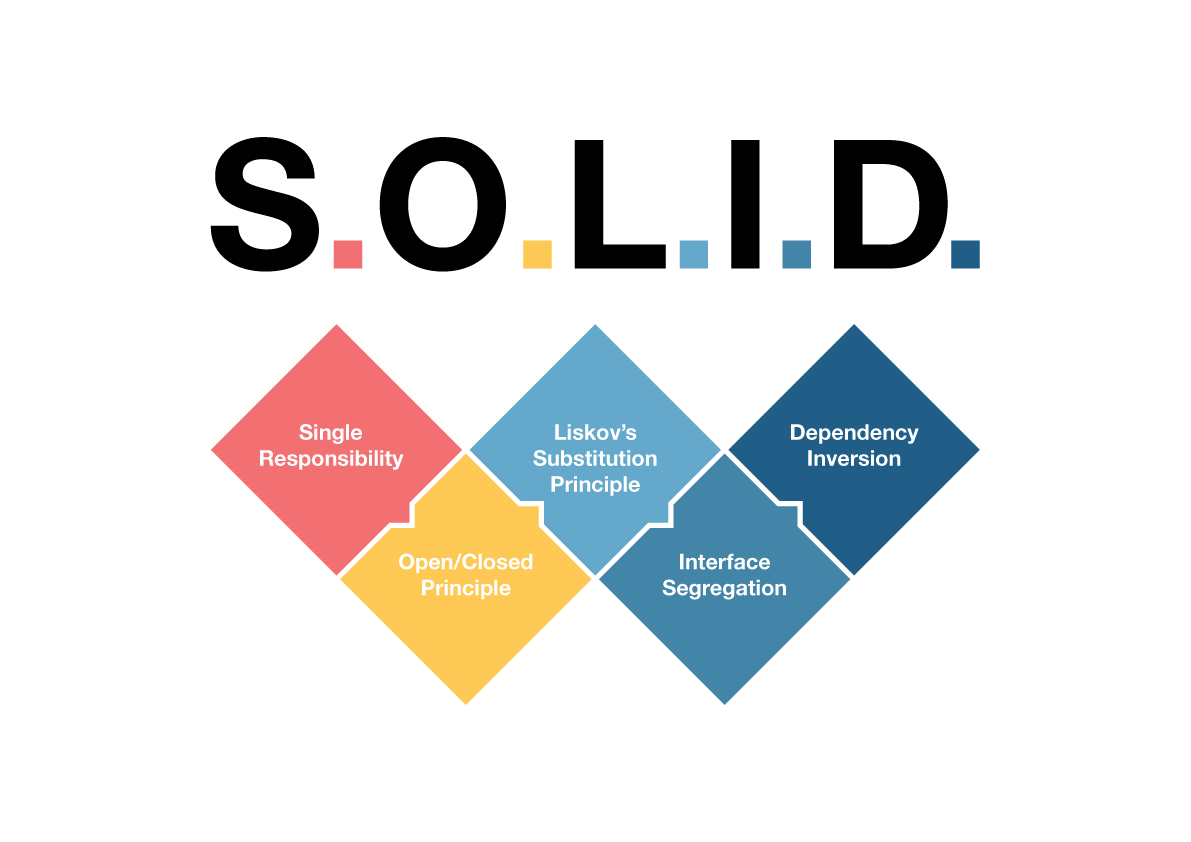

SOLID principles

The SOLID principles is a set of five principles suitable for object-oriented programming. Their goal is to make software design more understandable, flexible and maintainable. These principles highlight good practices to follow, but they are abstract, so there are several concrete patterns to develop while respecting these principles.

-

Single responsibility: Each file (class / function / module / section) must have a single responsibility, i.e. it must allow to do only one thing. Therefore, we must divide the logic into as many classes and files as necessary. In addition there must be a place for all types of files and each file must be in the right place.

-

Open-closed: Each class must be open for extension, but closed for modification. It should be possible to extend the functionality only by adding code but without changing the existing code. This is to minimize the risk of breaking the logic.

-

Liskov substitution: If B and C are implementations of A, then B and C must be interchangeable without affecting program execution. The implementations of B and C must have the same functions, signatures and types in order to be interchangeable. (Example: strategy pattern that we can go deeper into in another post)

-

Interface segregation principle: If B and C are implementations of A, then B and C must actually be able to implement the functions described in interface A. When executing our program we should not check if the implementation can activate this method. If this is the case, the solution is to split into several interfaces.

-

Dependency inversion principle: High level modules should not depend on low level modules, but both should depend on abstractions (e.g. dependency injection pattern).

Note: I will put together other posts to deepen each of them.

Pattern Strategy

Classification: Behavior

The strategy design pattern involves separating the execution of a business logic from the entity that uses it and giving that entity a way to switch between different forms of logic. For example, in order to perform different types of sorting on an entity, you must create an abstract SortingStrategy class or function and then create different sorting implementations. Now you can select the strategy by switching between the different implementations according to your needs.

Note: this one deserves an exclusive post, coming soon….

Composition pattern

Classification: Structural The inheritance offered by object-oriented programming can create tightly coupled hierarchical objects that are difficult to refactor, due to object dependencies. That is why we can use this composition pattern to be able to allow flexibility in what the container object can do. Basically we are talking about being able to group our components, and sub-group them as well, generating a sort of tree in terms of data structure. To put it in Creole, we can have products, which can be stored in boxes. And in turn, have boxes inside other boxes. If you have a case with multiple objects using the same interface, this may be the pattern that helps you to simplify the interaction between them.

Let’s go to the code (references here)

interface IProduct {

getName(): string

getPrice(): number

}

//The "Component" entity

class Product implements IProduct {

private price:number

private name:string

constructor(name:string, price:number) {

this.name = name

this.price = price

}

public getPrice(): number {

return this.price

}

public getName(): string {

return this.name

}

}

//The "Composite" entity which will group all other composites and components (hence the "IProduct" interface)

class Box implements IProduct {

private products: IProduct[] = []

contructor() {

this.products = []

}

public getName(): string {

return "A box with " + this.products.length + " products"

}

add(p: IProduct):void {

console.log("Adding a ", p.getName(), "to the box")

this.products.push(p)

}

getPrice(): number {

return this.products.reduce( (curr: number, b: IProduct) => (curr + b.getPrice()), 0)

}

}

//Using the code...

const box1 = new Box()

box1.add(new Product("Bubble gum", 0.5))

box1.add(new Product("Samsung Note 20", 1005))

const box2 = new Box()

box2.add( new Product("Samsung TV 20in", 300))

box2.add( new Product("Samsung TV 50in", 800))

box1.add(box2)

console.log("Total price: ", box1.getPrice())

Lazy pattern

The lazy design pattern allows to develop scalable and high performance applications because the principle of this pattern is to provide an application divided into independent parts. This allows to reduce the size of the main application and to have different modules that will be only downloaded by the user who only accesses that specific part of the app.

Singleton pattern

Classification: Creative This pattern ensures that there is only one instance of your class. Thanks to this singleton, you can control the scope of the variables inside it. The singleton is handled by a public getInstance method that guarantees the only way to access the class. In Angular, the dependency injection mechanism manages the pattern for us. For example, services provided in the root of the application are singleton instances, on the contrary, services provided in no components are singleton, and therefore, they will be instantiated by the injecting components.

Factory pattern

Classification: Creative This pattern is very simple but very useful when you need to instantiate different child objects of the same parent class according to certain conditions. The factory defines an object creation interface with the creation conditions as input and the object instance as output. This interface usually contains a single public method. Then, it is possible to have different implementations of this factory interface, each with its own logic to instantiate the objects. Note: this pattern applies when there is special logic for instantiating child objects, otherwise not.

For example, if you ever used or are familiar with something like:

const componentRef = viewContainerRef.createComponent<AdComponent>(adItem.component);

That’s exactly a factory developed by Angular, and that gives it to us to be able to implement the loading of components dynamically. Suppose we want to build a component of type Ad (advertising) to display banners, instead of generating static templates with these banners, we can make use of this factory to generate components that render different content to display dynamically. I leave you the official guide with the code here.

Decorator Pattern

Classification: Structural The decorator design pattern is an alternative to subclasses to extend an object using composition instead of inheritance. So, the idea of the decorator is to be able to add additional responsibilities to an object. The main concept is to have an object that wraps another object. The one that wraps the object is the decorator and is of the same type as the original object but also has an object of the same type as the object.

On one side we have the Typescript decorator (official docu here):

It is a one-time but permanent change, since the class that is decorated is different from the original class. And it is simple, basically a function. It occurs at compile time.

The common scenario is that a decorator is applied to different classes. For example: in Angular, the decorator @injector is applied to several classes and makes them injectable. We can also make our own custom decorators, which I would like to go into in detail in another post.

For the general pattern of decorators:

The common scenario is different decorators in a single class. We need to create a decorator class, a common parent class for the decorator class and the original class, and different child decorator classes. The original class remains unchanged and you can apply the decorator as you see fit during execution time.

Example: we have a coffee class. We can create different decorator classes: Espresso , Cappuccino, but we can also mix and match them: espresso + Cappuccino.

Let’s see a code example (I leave reference and more info here):

abstract class Animal {

abstract move(): void

}

abstract class SuperDecorator extends Animal {

protected comp: Animal

constructor(decoratedAnimal: Animal) {

super()

this.comp = decoratedAnimal

}

abstract move(): void

}

class Dog extends Animal {

public move():void {

console.log("Moving the dog...")

}

}

class SuperAnimal extends SuperDecorator {

public move():void {

console.log("Starts flying...")

this.comp.move()

console.log("Landing...")

}

}

class SwimmingAnimal extends SuperDecorator {

public move():void {

console.log("Jumps into the water...")

this.comp.move()

}

}

const dog = new Dog()

console.log("--- Non-decorated attempt: ")

dog.move()

console.log("--- Flying decorator --- ")

const superDog = new SuperAnimal(dog)

superDog.move()

console.log("--- Now let's go swimming --- ")

const swimmingDog = new SwimmingAnimal(dog)

swimmingDog.move()

Conclusion

Being able to know some of the design patterns that exist, gives us many opportunities not only to improve what we do, but to simplify and solve problems that we may encounter daily.

References of this post and to complement by here!

Happy coding! enter image description here